A powerful gamma-ray burst (GRB) that scientists observed in October 2019 was initially believed to result from a massive dying star exploding in a supernova in a distant galaxy.

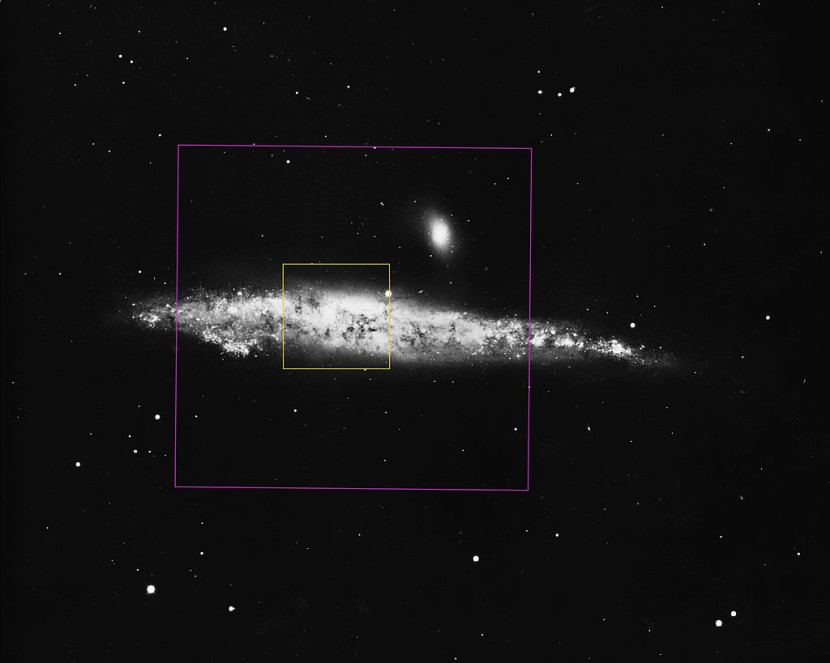

However, data from recently conducted observations revealed that the galactic event originated from a collision of stars, or their remnants, in a densely-packed area near a supermassive black hole. While researchers have theorized such a rare event, this is the first observational evidence that has been recorded.

Star Collision Derby

Gamma-ray bursts are extremely high-energy explosions that last milliseconds to several hours. Scientists classify GRBs into two classes as most, roughly 70%, are long bursts that last for more than two seconds and usually have a bright afterglow.

These types of explosions are commonly linked to galaxies with rapid star formation, and astronomers believe that long bursts are connected to the deaths of massive stars that collapse to form a neutron star or black hole. Alternatively, this could also happen when a magnetar newly forms, as per Ars Technica.

The recently formed black hole would be responsible for producing jets of highly energetic particles that move at near the speed of light. These are powerful enough to pierce through even the remains of the progenitor star, emitting X-rays and gamma rays.

On the other hand, gamma-ray bursts that last less than two seconds are considered short bursts and usually come from regions with very little star formation. Astronomers believe that these GRBs originate from mergers between two neutron stars or a neutron star and a black hole, resulting in a "kilonova."

The 2019 GRBs that NASA's Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory detected fall into the long burst category. However, astronomers were perplexed because they discovered no evidence of a corresponding supernova.

Powerful Gamma Ray Burst

A study of the recent discovery was published on Thursday in the journal Nature Astronomy. A co-author of the study, Wen-fai Fong, who is an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Northwestern University's Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, said that for every hundred events that fall under the normal classification scheme of GRBs, there is usually one odd event, according to Yahoo News.

Fong noted that these unforeseen events provided researchers with more data about the spectacular diversity of explosions that the universe is capable of producing. Over time, astronomers have observed what they categorize as the three main ways that stars can die, which depend on the celestial object's mass.

Those with lower mass, such as our solar system's sun, start to shed their outer layer as they age and eventually transform into dead white dwarf stars. On the other hand, massive stars continue to use fuel-like elements inside their cores and later explode, an event called a supernova.

Another co-author of the recent study, Giacomo Fragione, a Northwestern astrophysicist, said that the findings of such extraordinary phenomena within dense stellar systems are exciting discoveries. He argues that it provides a glimpse into the intricacies at work inside these cosmic environments, said Phys.org.

Related Article : Himalayan Glaciers On Track To Lose 80% of Ice by 2100 if Global Warming Continues

© 2025 HNGN, All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.